How does a Pinlock visor work?

Published on: 19 April 2018

When a helmet fogs up, it is the result of condensation. Condensation occurs when warm, moist air comes into contact with a surface that is colder than it is. This air is unable to retain the same amount of moisture as it did, and the water in that air is released onto the colder surface, forming a damp film.

When a motorcycle visor fogs up, therefore, it is because the hot and moist air that has been expelled from the nose and mouth has come into contact with a cold visor.

Open the vents in a helmet and the incoming air will help move the warm air away from the visor. The cool air will also reduce the temperature of the air you are breathing out, reducing the differential between the external and internal temperatures. This reduces the potential for fogging.

In a helmet with poor venting, cracking the visor open a little will have the same effect, although this may not be an ideal solution in wet conditions. A nose guard that deflects your breath downwards may help. Alternatively, you can consider removing the internal chin curtain to allow your breath to exit the helmet more efficiently.

Some helmet visors come with an anti-fog coating, but these coatings are rarely particularly effective, and normally wear out over time. But, in essence, the laws of physics mean that all helmets, dependent upon the conditions, can and will fog up.

If a visor fogs up it is not, in truth, the helmet’s fault, but some helmets will fog up more easily and quickly than others. Ironically, cheaper helmets that don’t fit as well, and that are not as well sealed, are probably less prone to fogging.

Top quality helmets like the Schuberth C5 or Shoei Neotec 3 may be more prone to fogging because they fit tightly around the neck and often have flaps and inserts to stop air entering the helmet and creating noise. Of course, if air cannot easily enter the helmet, it equally cannot escape. And if hot air cannot escape, condensation becomes more likely.

Other than opening the vents, or even the visor itself, the only way to prevent condensation from forming on the inside of the visor is to fit a Pinlock anti-fogging insert.

Not every helmet out there can take a Pinlock. The cheapest helmets tend not to be able to. The same goes for most ‘Sunday Morning’ style helmets, where the expectation is that they’ll one be worn on warm and dry days.

To fit a Pinlock insert, a visor has to be fitted with two pins, between which the insert is fitted. Some helmets come with a Pinlock in the box; others come ‘Pinlock-ready’, which means they have the pins in place but the insert will need to be purchased separately.

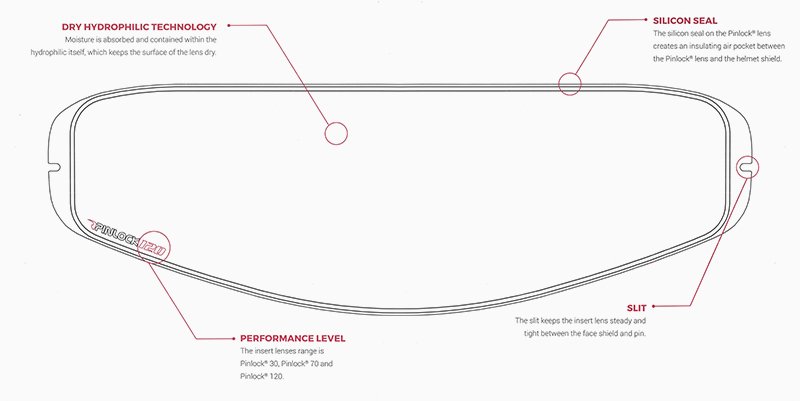

The Pinlock insert has two key features or attributes that allow it to do its job.

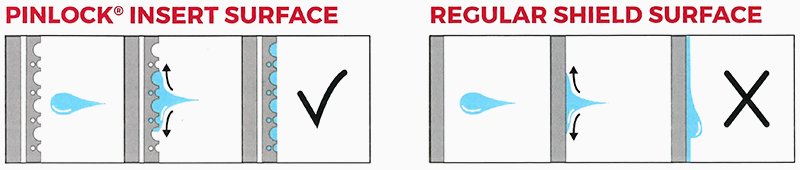

The first is the construction of the insert. It is hydrophilic which, in essence, means that it absorbs moisture. Because the moist, hot air from your breath does not sit on the surface of the insert, but rather is absorbed by it, condensation does not form.

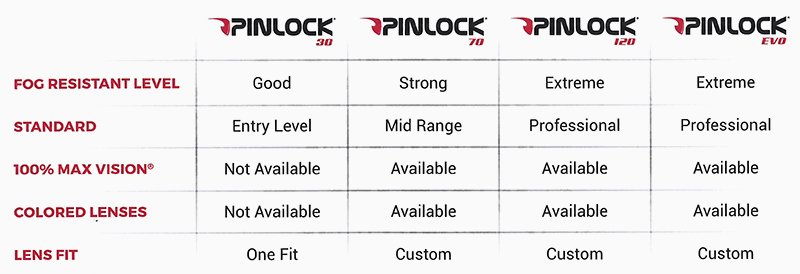

Pinlock offers three different performance levels of insert. There’s the Pinlock 30, the Pinlock 70 and the Pinlock 120. The higher the number, the more absorbent, and therefore more effective, the insert is. The number actually relates to laboratory testing, and the time it takes for the visor to become saturated.

So a 70 Pinlock is, in theory, twice as effective as a 30 Pinlock, and only half as good as a 120 Pinlock. An Evo Pinlock, by the way, is merely the name given to the 120 Pinlocks supplied in Shoei helmets.

According to Pinlock, the 70 model is the most widely fitted, and is perfect for commuting. The 120 Pinlock is designed for racing or adventure riding where the temperature differentials might be greater.

But our position is that, with the conditions we experience in this country, we’d always go for a 120 Pinlock. It’s only a few quid more and, in some scenarios, the difference could be a life saver. It’s a no brainer, in our view.

Now the second key component within a Pinlock is the bead that runs round the edge of the insert that prevents it from coming into contact with the external visor. Some people refer to Pinlocks as having a double-glazing effect, and it is the separation of the insert from the external visor that gives the Pinlock this quality.

On a cold day, the air hitting your external visor can be very cold indeed, especially given the wind-chill factor. When a very cold surface comes into contact with the warm air, your breath, condensation results. But by keeping the insert away from the visor, it stays warmer, this diminishing the potential for fogging.

Now Pinlock is not the only company that produces anti-fog inserts. There are companies that make cheaper versions that make use of the Pinlock pins.

But these cheaper ones are cheaper for a reason and, in our experience, they simply don’t work. And the main reason is that the beading around the edge of the insert is plastic as opposed to silicone.

The silicone beading on a genuine Pinlock is important because it effectively glues the insert onto the outer visor. This is important because if there’s a gap, the warm air from your breath will come into contact with the cold air from the external visor, allowing condensation to form.

But surely, you might ask, if the cheaper Pinlock lookalike insert is properly adjusted, using the ‘eccentric’ visor pins, should it not always seal tightly?

But this is not the case because Pinlocks expand and contract as they first absorb moisture and then subsequently dry out. That is to say that, when the Pinlock is loaded with water, it expands. As it dries out, it shrinks.

The silicone bead on a genuine Pinlock allows the insert to grow and shrink without breaking the seal. With the cheap lookalikes, the expansion and contraction creates gaps. And where there’s a gap, there will be fogging.

It’s why, in our book, it always makes sense to fit a genuine Pinlock. They simply work better.

So what else do you need to know?

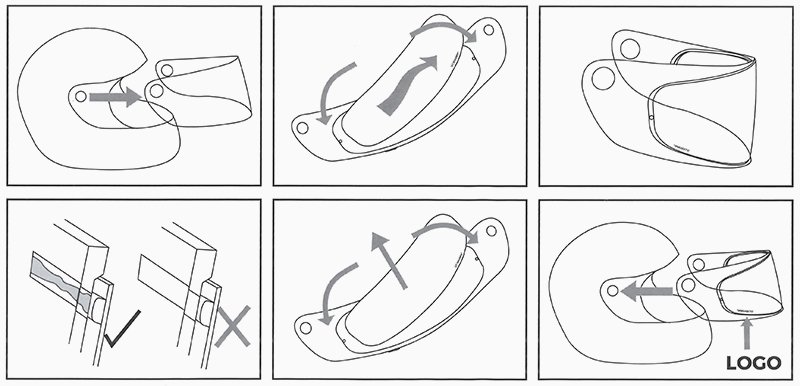

We’ve already mentioned the ‘eccentric’ pins, so let us explain what they are. These pins have a shaft that is thick on one side than the other. This allows you to tighten your Pinlock into place so that it firmly grips the outer visor. If the Pinlock will not sit flat inside the visor, you might conceivably need to loosen tension on the Pinlock by turning the pin, thus increasing the space between the two pins. It’s not rocket science and, in fact, it sounds more complex than it is. But the end result is that the beading on the Pinlock should sit flush against the visor.

Finally, although it’s very rare, it’s possible for even a 120 Pinlock to reach its saturation point, where it can no longer absorb any more moisture. This might happen in prolonged rain, or in the cold when you are working particularly hard on the bike, or when you’re wearing a helmet that is poorly vented.

In such circumstances, you need to remove the Pinlock. You can clean it with soapy water for good measure, but then leave it to dry naturally. You should do the same with the external visor, again allowing it to dry out. Once dry, the Pinlock will do its job again. This having been said, a Pinlock will eventually pack up and, of course, this depends on the mileage you ride, and the conditions in which you ride. If you ride every day, often in cold and wet conditions, you might need to replace the Pinlock after a year or two.

But the bottom line is this. If you don’t want to experience fogging on your helmet buy a helmet that is at least Pinlock ready. And then, if one is available, fit a 120 Pinlock; it’s worth the money.

And if somebody in a shop tries to tell you that the unbranded Pinlock that comes with a helmet is every bit as good as a genuine Pinlock, tell them that’s a load of b*******.

There is only one anti-fog visor that really works. And it’s made by Pinlock. Job done.

You can browse all our available PInlocks and other helmet accessories and spares here.