- Menu

- JacketsMotorcycle Jackets

- HelmetsMotorcycle Helmets

- GlovesMotorcycle GlovesOther Categories

- BootsMotorcycle BootsOther Categories

- PantsMotorcycle PantsOther Categories

- JeansAll Motorcycle JeansOther Categories

- AccessoriesAccessoriesAccessoriesMotorcycle Luggage

- Ladies GearLadies Motorcycle Clothing

- Brands

- Sale

- Editorial

- Videos

- Sign In

- Register

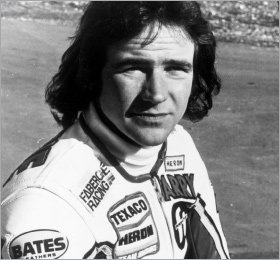

Motorcycling 1985 to 2010

An Obsession with Road Racing

It would be true to say that from the moment the motorcycle was invented, there was a will to make it go faster, from which followed the desire to race one machine against another.

The first Isle of Man TT races, for two different classes of touring motorcycles, were held in 1907, and throughout the twentieth century racing was a prominent feature of the motorcycle world. It was fun to watch, and exciting to take part in. For the manufacturers it provided a platform for improving the performance of their machines, and it is undoubtedly true that the high performance bikes we ride on the road today owe much of their sophistication to the innovations that came about through racing.

It was in 1949 that the FIM Motorcycle Grand Prix World Championship was inaugurated; it is a series that is still running strongly today.

Britain had always had a strong association with racing, and from the very early days domestic riders figured prominently in the sport.

These British champions, as you might expect, became heroes for many road-going motorcyclists. They were household names, and the manufacturers revelled in the glory that their track victories brought them.

But it was the success of a new championship that raised the interest in track racing to a totally new level.

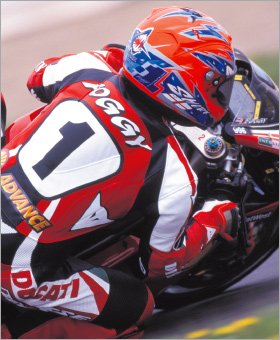

The World Superbike championship was founded in 1988, but what made the series so unique was that the bikes that raced in it were essentially tuned versions of the motorcycles that were available for sale to the public.

In 1988 and 1989, the title was taken by American Fred Merkel on Honda's now iconic RC30, a machine that was almost identical in nearly every respect to the bike that could be purchased by anyone with a motorcycle licence at their local Honda dealership.

The same applied to the Ducatis, Kawasakis, Suzukis, Yamahas and Aprilias that have taken every title since.

Riders thrilled to see the bikes they rode on the road being pushed to their limits on the circuit. TV audiences boomed, as did sales of the bikes that mirrored those that raced in the series. And if the large capacity machines that replicated the racers were out of reach financially for some, the motorcycle industry met the demand with bikes of a smaller capacity that nonetheless remained true to the ethos of their larger siblings.

So adoring was the British public of the bikes and riders who participated in both the World Superbike series, and the UK based series that adopted the formula in 1993, that it became somewhat 'de rigeur' for many motorcyclists to ride a race replica bike on the road.

Seemingly overnight, every enthusiastic motorcyclist became a budding road racer.

The standard form of dress became the one piece leather suit. The helmets that sold best in motorcycle dealerships were those that bore the graphics of the leading riders. And, of course, no rider's outfit was complete without the addition of a pair of racing gloves and boots, all adorned with the protective features required by the professionals.

Unfortunately, perhaps, for the reputation and safety record of motorcyclists, this phenomenon spawned a new style and approach to riding.

The Sunday morning ride became not an opportunity to get into the countryside for some scenic vistas and fresh air, but rather an opportunity for a race.

Clad in a racing suit, and sat astride a machine often capable of a speed well in excess of 150 miles an hour, it was inevitable that riders would want to explore the capabilities of their bikes.

Of similar import was the need to demonstrate that you could pull away from the traffic lights, balancing the bike balletically on the back wheel. Those who found the task more challenging were able to take lessons at the various 'wheelie' schools that sprung up around the country.

Not, of course, that the World Superbike Championship was the only series that influenced riders. The blue riband bike racing series had historically always been the Grand Prix 500cc championship for prototype bikes.

World Superbikes definitely dented the popularity of Grand Prix racing. Even more so than in the car world, World Superbikes allowed the enthusiastic motorcyclist to watch a bike win on Sunday, and then buy it on the Monday.

The popularity of the long established Grand Prix motorcycle championship was rescued, however, by one rider: Valentino Rossi.

But as the decade ended, and Valentino's domination started to decline, slowly but surely the obsession with road racing that had driven the motorcycle industry not only in Britain, but worldwide, began to diminish also.

In a world concerned about the greenness of the environment and global warming, a world in which speed and the excessive consumption of fossil fuels had started to become socially unacceptable, it was perhaps inevitable that a new aesthetic would emerge.

Sales of sportsbikes went into decline, and riders started to look around for alternative ways to get their motorcycling kicks.

Images courtesy of www.mortonsmediagroup.com