Stuff you should know about motorcycle helmets

Published on: 20 June 2018

Over the last month or so we’ve been on a bit of a mission; a mission to learn more about the dark arts involved in the making of motorcycle helmets. We sell a reasonable number of helmets here at Motolegends and, whilst we feel our product knowledge isn’t bad, we came to realise that there’s a lot we didn’t necessarily know or understand about helmet safety.

It all started with conversations we had with customers about how they could tell if a damaged helmet was okay to ride in, and whether, for example, a 10 year old helmet was still protective. We set up meetings with some of the leading European players, and we ended up learning lots of stuff we never realised we didn’t know. It’s been an interesting journey, and we want to share our findings with our customers.

Funnily enough, however, we couldn’t get any meaningful or useful advice from the manufacturers about how to tell whether a helmet was still safe. Would dropping a helmet three feet onto a concrete floor render it unusable? Or would it have to be higher? Or lower?

Nobody we met with was willing to give us an answer. It depends on a number of factors, we were told, but we couldn’t get a straight answer. Now whether that’s because this really is a complex matter, or whether it’s because the manufacturers are always going to have a vested interest in claiming that a helmet is unusable, we don’t know.

Some even felt that a helmet falling off a bike seat on onto concrete floor could render it unsafe for future use. The only way to really tell if a helmet is compromised is to X-ray it, but that’s never going to happen if you’re a road rider, so it is almost impossible to come to a definitive view.

What everyone was clear about, though, was that if you cracked your head against the tarmac in a road accident, the helmet would almost certainly need to be replaced even if, after the event, you thought it had not been a hard contact.

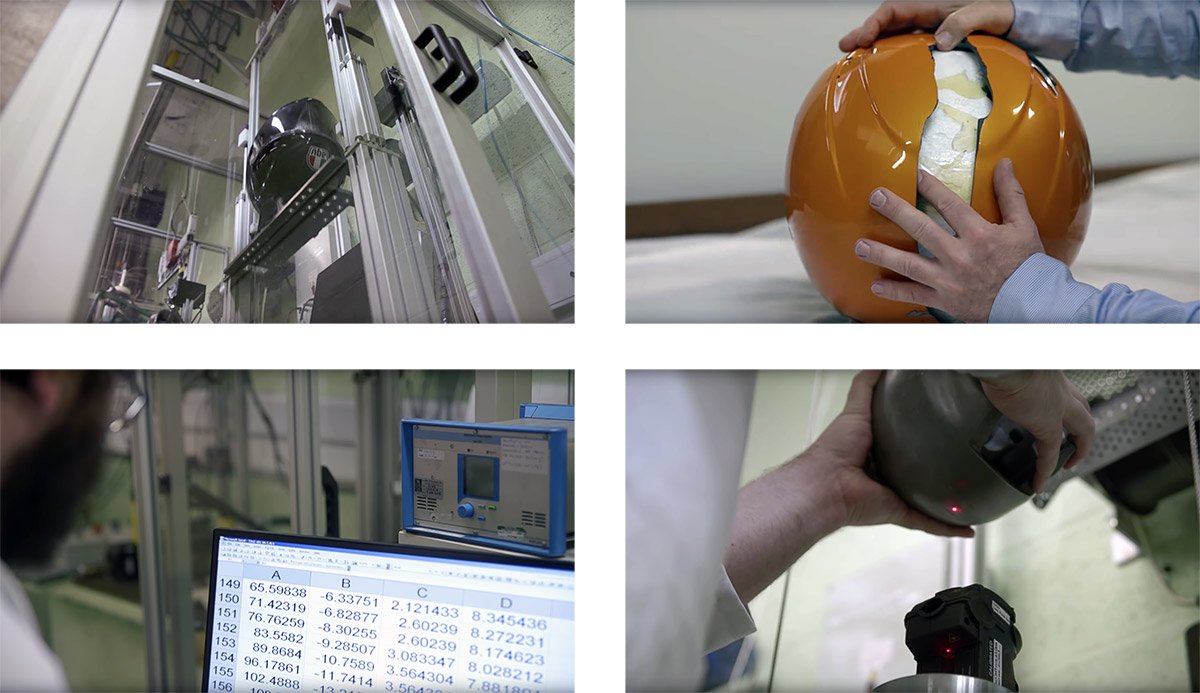

Any impact that caused any kind of crack in the outer shell would also, we were told, toll the death knoll for a helmet, for it’s the shell that absorbs the first impact, and if its integrity is compromised it simply wouldn’t do its job.

So, sorry, we still can’t answer the oft-posed question about whether a damaged helmet needs to be replaced. A low fall onto a muddy or grassy surface is clearly not going to be an issue, but if we are to believe what we were told even a metre or so onto a concrete surface could compromise a helmet’s protective qualities.

The next question we asked everybody was about the longevity of helmets, and when it needs to be replaced. Again the answers seemed to resemble the conundrum about the putative length of a piece of string.

One manufacturer was, however, prepared to commit that, in a European climate, its helmets could be guaranteed to do their job for the duration of its five-year warranty. They could make no further comment other than to point out that, in some hotter and more humid parts of the world, a helmet might not even last that long. And in some such markets, this company only offered a two-year warranty.

Surely one could tell if a helmet was safe, we postulated, by pressing the eps to see how soft it was. If it was soft, the helmet was still capable of performing its primary function, we suggested. ‘Certainement pas’ was the emphatic Gallic response.

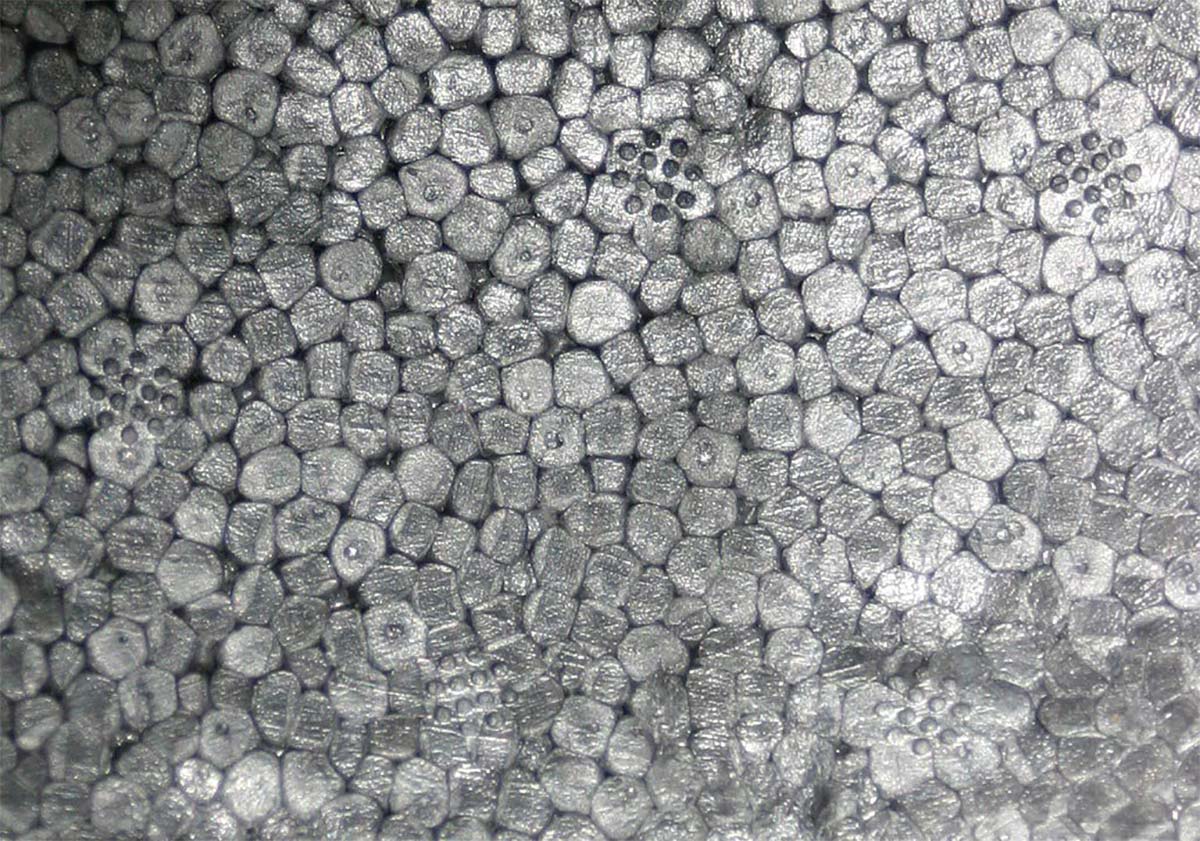

So where we get to is that, if you ride somewhere between 5,000 to 10,000 miles per year, your helmet is probably more than up to protecting you for the full five years.

But if you commute a couple of hours a day, every day, the life of the helmet might be less, and that’s because the sweat that’s generated permeates into the eps, causing it to shrink and harden. So, for some high mileage riders, a new helmet might be deemed beneficial after, say, three years.

But whilst nobody gave us very satisfactory answers to our safety questions, we did learn a lot from our visits that was both interesting and useful.

One particular question we did ask was whether a lighter, carbon-shelled helmet was safer than a heavier, fibreglass one, for example. Reluctantly, most agreed that such helmets weren’t any safer. Racers wear lightweight, carbon helmets because lightness equates to speed, but also because, at extreme g-forces, a lighter helmet puts less pressure on highly stressed neck muscles. Road riders buy carbon helmets because they want to show off, or perhaps because they mistakenly believe they are buying something safer. The truth, sadly, is that they’re not. In some cases, quite the reverse.

It was important, everybody told us, to make sure that the fit of a new helmet is right. That a helmet is snug around the forehead, but not tight. That the face is firmly clamped by the cheekpads so that in an accident the helmet does not twist. Or worse, come off. This we always knew. It’s why we are at times surprised that so many people buy helmets over the internet without trying them on.

Come visit us, and we make sure a helmet fits properly. If a specific helmet doesn’t work, we’ll tell you, and point you in another direction. A lot of people buy poorly sized helmets. Sometimes they go too big because they desire comfort above all other considerations. Sometimes they buy too tight because they know no better. In our view, a helmet needs to be properly fitted by somebody who knows what they’re on about. And it will often take a while to get it right, as one tries different headlinings and varying thicknesses of cheekpad.

But we can only do this if the headlinings on a helmet can be replaced, and if different cheekpads can be fitted. It’s not always the case. Take the Bell Custom 500, open-face, for example. It either fits or it doesn’t. We can do nothing to make it a little looser or a little tighter. It stands in stark contrast to, say, Shoei’s JO, where we have three different headlinings and four different cheekpads.

It’s a not disimilar situation with the Schuberth C4. This is not a cheap helmet. It’s been in the market for a couple of years, but Schuberth still hasn’t supplied retailers with different cheekpads or headlinings. In our view, if a helmet doesn’t present the option to have its internals exchanged for different sizes, you can be reasonably confident that considerations of safety are not central to the company’s thinking. Again, the Shoei equivalent, the Neotec 3, gives us a huge variety of combinations to ensure a near perfect fit.

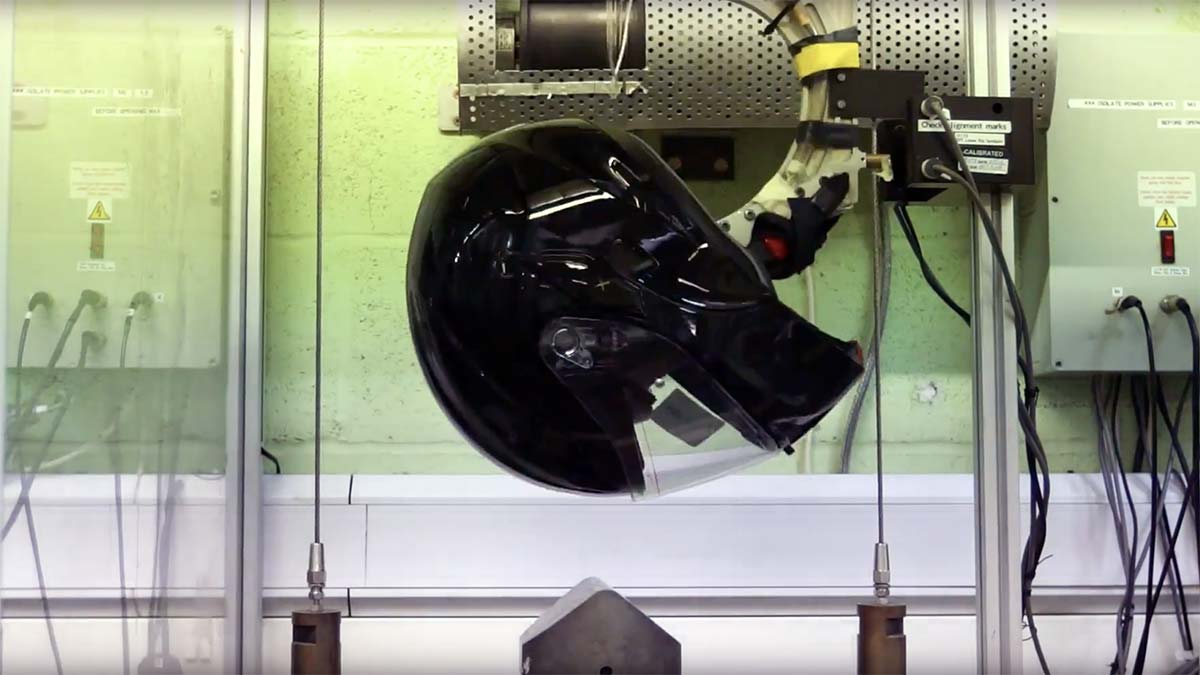

The European safety standard, ECE22/O5, everybody seemed unanimous about, is much safer for motorcyclists than the American DOT standard.

And that’s because the American standard, which came out of work done by the US Snell Foundation, is more applicable to car racing than to motorcycle riding. In car racing, the helmet can often find itself subjected to multiple impacts in the same place; for example, banging repeatedly against a fixture like a roll bar.

DOT approved helmets are, therefore, very strong and will take numerous impacts in a given area. But that doesn’t tend to happen when you come off a motorbike. More importantly, a hard shell of the kind needed to pass the DOT tests will often not absorb an impact particularly efficiently. It will actually transmit it, potentially causing the brain to rebound hard against the opposite side of the skull.

This was new to us. We had often looked at DOT helmets from people like Biltwell, and whilst we had subjectively felt that we wouldn’t want to ride in one, it wasn’t until the different test methodology was explained to us that we understood why.

We are, we have to admit, sometimes surprised by the extent to which some motorcyclists are prepared to place style above safety. Wearing an illegal DOT helmet is, in our opinion, a step too far. We have people who come into the shop in Guildford wearing some kind of Harley-style skull cap or German stormtrooper affair; and it’s clear that, in any kind of incident, they’re not going to provide much by way of protection.

Plus, of course, if you do have an accident, and the other side’s lawyers find out you were wearing a DOT helmet, perhaps from a Police report, you could well find that your insurance pay out would, at the very least, be reduced.

And, as for retailers who sell DOT helmets, we have nothing but scorn. The job, on our side of the fence, is to help protect customers. Selling illegal, below-standard helmets is just irresponsible and ethically dubious; not to say somewhat stupid from a liability standpoint.

What some people point out, of course, is that the DOT standard must be reasonably robust because it applies to millions of riders in the US. Now I don’t want to get political here, but we’re talking about a country that deems it safe for the man on the street to own an automatic weapon. The same country where, in over 20 states, you don’t even need to to ride in a helmet. It should be of no surprise, therefore, to learn that the safety testing of motorcycle helmets is not a particular priority for the American authorities.

The subject of the ECE standard did throw up other issues, however.

The fact is that even the European standard is not, in itself, particularly demanding. It represents the minimum standard that is required to sell a helmet in the EU. It is not the standard that the major manufacturers test to. It is the base level, not the optimum one.

It explains why you can buy £50 helmets in supermarkets and over the internet that meet the standard. The fact that a bargain basement helmet carries the same safety certification as a £500 Shoei doesn’t mean it meets the same safety standard. It doesn’t. A helmet that only just meets the standard might be legally saleable, but it doesn’t mean that you’d want to wear it. In fact, you almost certainly wouldn’t want to.

There are, in the helmet world, those companies that are focussed on safety; companies that employ their own technical and R&D staff; companies that make their own helmets in their own factories, and that strive to improve the quality of the products they make. We’re talking about the big players: Arai, Shoei, Schuberth, AGV, Shark, Nolan, Nexx and the like.

And then there are those companies who apply their logo to a helmet made by an anonymous factory in somewhere like China or Vietnam. Their helmets might meet the EC’s basic safety standard, but you can be pretty sure that these factories don’t have a huge R&D facility dedicated to improving safety standards, because their overriding obsession is price.

But, to make matters worse, there’s a further sting in the tail. A few years ago, the Italian version of Which magazine independently tested a number of cheaper helmets that supposedly met the ECE22/O5 standard.

More than half of them failed to come up to scratch. And that’s because the standard is self-certified. Once a helmet design has been tested and approved, no further checks are applied by the authorities. If a manufacturer takes the decision to cut corners, it will probably get away with it. The big players randomly test hundreds, even thousands, of helmets a year. Those who use independent factories almost certainly don’t.

It reminds me of the old adage that if you’ve got a ten dollar head you should wear a ten dollar helmet. We always believed, or wanted to believe, that it was worth spending more money to get a better helmet, but our research and conversations have cemented our views.

One thing we were keen to discuss with the manufacturers was the relevance of the UK-specific SHARP ratings, and what manufacturers think about the standard. As a retailer, we’ve never been convinced about their relevance, as some very reputable helmets do not achieve high ratings, whilst some rather cheap helmets score five stars.

SHARP is a Governmental body created to replace the British Standard that existed before we became members of the EU. Some manufacturers are very much in favour of the SHARP standard. One manufacturer we met is so enthusiastic about the SHARP regime that it uses the star ratings on all the helmets it sells around the world. But not every manufacturer is so convinced.

The SHARP test, it would seem, can be prepared for, and it appears likely that some manufacturers have specifically developed helmets that score well in this particular test protocol, by placing extra material in the areas that SHARP targets in its testing.

The test itself rewards helmets that are effective at absorbing the energy involved in an impact. And this of course is a good thing. It’s a philosophy that comes out of the NCAP style of testing that applies to cars. Many years ago, the car manufacturers built large, immensely strong cars as a means of surviving accidents, but then it was realised that it was safer to have crumple zones that gradually absorb the energy of an impact.

A helmet that absorbs, rather than transmits, impact energy will slow down the movement of the brain as it travels from one side of the skull across to the other. Now obviously that’s a positive thing, because a brain bouncing around a skull is not conducive to good mental health.

The helmets that are the best at absorbing energy have soft shells. But the issue is that a helmet can have a shell that is too soft. And that’s because a soft shell may actually crack when it is impacted, and if a shell has cracked it will not be effective against a second impact in another area. Interestingly, this is often what happens in an accident. There’s an impact on one side of the helmet and then, as the rider rolls or tumbles, there can be a second impact. A soft shell therefore is not necessarily what we want as motorcyclists, even though such helmets will often score highly in the SHARP tests.

The other side of the coin, as we have already alluded to, is helmets with very hard shells. Helmets designed for the US market, where the DOT standard is the norm, will often not absorb energy particularly well, and will not score so well in the SHARP tests.

The answer, clearly, is a shell that is soft enough to absorb energy, but hard enough not to crack on impact. But it’s not really possible for us, as consumers, to know whether a helmet has a hard, a soft or a medium density shell.

What it probably does suggest is that if we really want to protect ourselves properly we should put our faith in those manufacturers with the commitment and in-house facilities to develop and test for safety. Not all manufacturers do have such resources. In fact, by far the majority don’t.

What we learned suggests, to us, that whilst the SHARP test regime is useful, it only tells part of the story. And certainly, we are not convinced that we would personally be overly swayed by a helmet’s SHARP star rating.

Not every motorcyclist, it has to be said, chooses a helmet on the basis of its safety credentials. We have no problem with this. Riding a motorcycle says something about a person’s attitude to risk. If you are totally risk adverse, you don’t ride a bike; it’s that simple.

And, at times, we all make decisions about our riding gear that place style and comfort above safety. But whilst this is easy to reconcile when you purchase a pair of trainer boots or lightweight gloves, many riders fail to realise that not all helmets are equally safe. Indeed, in relative terms, some are not really up to the job at all.

We know that money can be tight; obviously we do. But economising by riding in a cheap helmet is, we reckon, a foolhardy economy. Motorcycles are great, but actually the real fun comes from riding them. And if you ride them, there’s a chance that one day you might fall off one of them. And If that does happen the part of your anatomy that is most in need of protection is your head. And if that’s not worth paying a few hundred extra quid for, then we don’t know what is.

Let’s put some numbers on it. Paying under £100 for a full-face helmet is bonkers, in our opinion. We don’t reckon you get into respectable protective headwear until you’re paying a couple of hundred quid for a full-face helmet.

And personally we reckon, on a proper road bike, that we wouldn’t feel properly protected until we were paying in the region of £250. £300 plus buys you a decent, reliable, and properly protective helmet. Ironically, paying twice that amount doesn’t necessarily get you anything better. It might even buy you something worse.

I suppose our conclusion is that if safety is paramount, it’s worth sticking to the well known brands with a heritage in racing of some description. If you want to spend £500, £600 or more on a helmet purely on the basis that it looks funky, or has an exotic, hand finished interior that’s a personal decision, but in making that decision there’s a trade off; not just in comfort and wearability, but almost often in terms of safety too.

Not sure what motorcycle helmet to buy? We have a great article: How to choose a motorcycle helmet.

CLICK MOTORCYCLE HELMETS TO SHOP